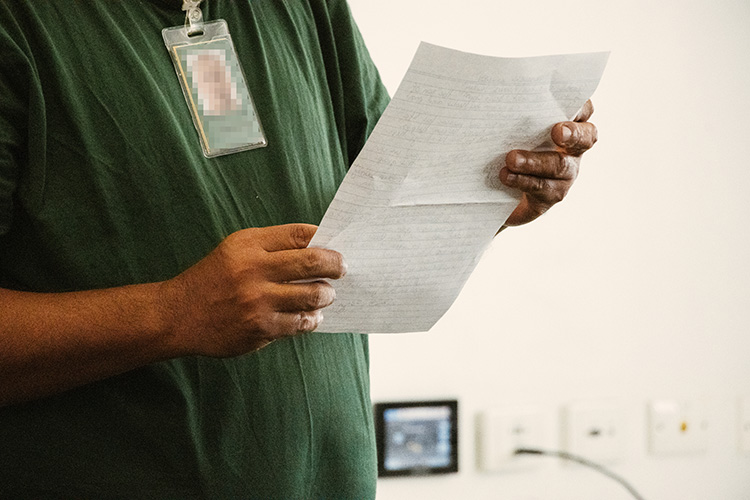

Stories of hope

Statement about crime

Prison Fellowship Australia acknowledges those affected by crime, both directly and indirectly. We never condone any criminal activity, while remaining committed to walking alongside prisoners, ex-prisoners, their families, and victims. We share stories of their journey towards wholeness, to highlight God’s goodness and His desire for reconciliation with both Himself and others.